The World Is Getting Fatter

All around the world, people are tipping the scales more than ever before. The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) report 2025 on global childhood nutrition shows that the number of overweight children has doubled over the last 25 years. According to UNICEF, this marks the first time in history that more children are obese than underweight. Packing on the pounds is an alarming trend that is especially pronounced in low and middle-income countries. This development impacts not only children, but adults as well.

Prosperous countries are also seeing a rise in the number of people who weigh too much. Swiss Federal Office of Public Health figures show that 43 percent of the population is overweight, including 13 percent who are considered obese – twice as many as three decades ago. Being overweight or obese is a heavy burden for the body that comes with severe health consequences. It increases the risk of developing cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and even some forms of cancer.

We eat too much and move too little

But why is the world getting fatter? There are many reasons for this phenomenon. “The main problem is that we are taking in much more energy than we are burning off,” says UZH veterinary physiologist and nutrition researcher Thomas Lutz. “In other words, we simply eat too much and move too little.” And we don’t always eat what’s actually good for us. Many foodstuffs contain excessive and highly concentrated amounts of carbohydrates, sugar and fat. This means that you only need to consume very little in order to take in large amounts of energy.

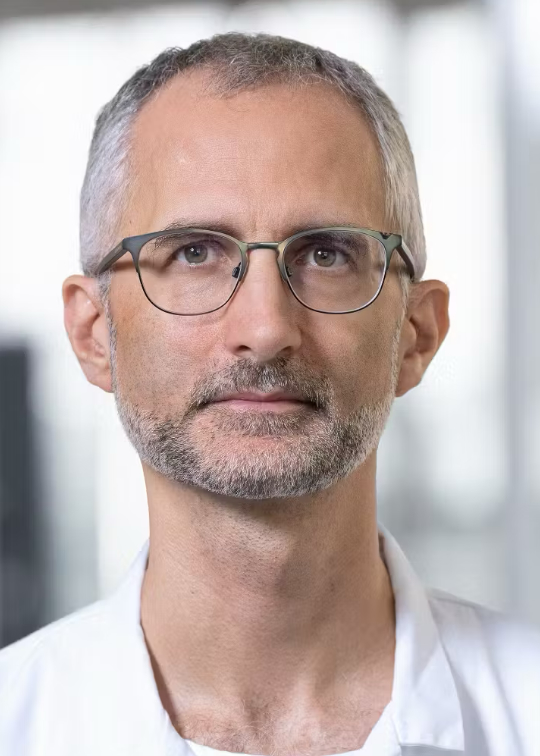

Research Spotlight: Physiologist Thomas Lutz and obesity specialist Philipp Gerber are researching how overweight people can get back on track. (Video: Katharina Weins, UZH Kommunikation, Angela Spörri MELS UZH)

These calorie bombs are sometimes quite unassuming, as well. It’s not only industrially produced junk food that’s calorically dense, but also some foods that appear healthy at first glance, like fruit juice and protein shakes. “You should question any liquid nutrients that don't naturally exist in that state,” says obesity specialist and UZH adjunct professor Philipp Gerber. Fruit juice causes short-term spikes in blood sugar without the accompanying plant fiber that would be needed for slow and thorough digestion. “Food processing has resulted in foodstuffs that don’t correspond to our biological setup,” says Gerber. “Generally speaking, we should be eating less carbohydrates and opting for more whole grain products when we do eat them.”

Our bodies are programmed to avoid starvation. They aren’t really made for an environment of dietary surplus that’s typical of our lives today.

From a physiological perspective, we are still hunters and gatherers. Our ancestors nourished themselves on roots, plants and the occasional piece of meat, regularly going longer stretches without food – a way of life that is also reflected in our biology. “Our bodies are programmed to avoid starvation,” says Lutz. “They aren’t really made for an environment of dietary surplus that’s typical of our lives today.” Our nutrition is regulated by a biological program, part of which is steered by hormones that influence our eating habits and control how much energy we need and expend. Lutz has conducted a great deal of research into how these signaling molecules work.

One of these is called leptin. If the body has too little adipose tissue for storing energy, the leptin level drops, which triggers a search for food. “This hormone is a wonderful biological sensor that protects us from starvation,” says Lutz. However, it doesn’t work well in the opposite direction; if leptin levels rise because we have too much fatty tissue, there’s no corresponding “stop” signal to halt the excess intake of nutrients. This is a mechanism that wasn’t selected for by evolution, so it appears to work poorly in times of abundance.

Amlyin, another hormone that plays a key role in our nutritional physiology, has also been a focal point of Lutz’s research career at UZH. This hormone is released together with insulin when we eat, regulating satiety, slowing gastric emptying and preventing the secretion of glucagon, a hormone that drives up blood sugar levels. Amylin also impacts the reward centers in our brains. Whenever the body produces more, our cravings for energy-dense nutrients like sugar and carbs are reduced. This is how amylin works as part of a biological system responsible for keeping energy intake and expenditure – or put differently, hunger and satiety – in the healthiest possible balance.

Obesity is a chronic illness

For people with obesity, this balance becomes completely disrupted. Feelings of fullness don’t kick in even when the body has taken in enough energy. This has a lot to do with an individual’s biology. “One study on sugary drinks showed that people with favorable genes were able to drink a lot of these beverages while still keeping their energy balance relatively stable,” says Gerber. The excess carbohydrates were compensated for by eating less of them later.

For the obese, this balance works poorly – or not at all – based on genetic factors. “We can’t will ourselves into feeling full,” says Gerber. That’s why Gerber and Lutz see obesity as a disease and not a character flaw, which is consistent with the World Health Organization’s stance that obesity is a chronic illness. “People aren’t solely at fault for their obesity,” says Gerber. Prejudices against obese people are still widespread, however, despite being unjustified.

Inject your way to weight loss

Employing different angles in their research, Lutz and Gerber both tackle the question of how to successfully combat excess weight and restore the body’s energy balance. Lutz’s basic research on amylin in his role as a veterinary physiologist has paved the way for the development of new anti-obesity medications. Satiety hormones can help reduce body weight. A weight loss injection with a novel compound based on amalyin is about to receive approval. Other drugs that promote satiety and dampen appetite are already available on the market.

“Compared to existing meds, amalyin-based compounds have fewer side effects, going off the current state of evidence,” says Lutz. “They cause less nausea, for instance.” For Gerber’s clinical work at the Obesity Center of the University Hospital Zurich, prescribing weight loss injection therapy is a key pillar of treatment that complements nutrition counseling, social and psychological support and in particularly severe cases, gastric bypass operations. “These injections can help reduce patients’ weight by up to 20 percent on average,” he says. “They’re an effective tool for combating obesity, but not for use as a lifestyle drug.”

Diets need to be both effective and feasible. Otherwise they’re pointless.

Weight loss injections only work as long as you use them. If the drug is discontinued, patients typically re-gain the weight, meaning that the drug needs to be taken permanently. This isn't always possible, however. Currently, health insurance only covers three years of costs for prescribed injections. After that, patients have to foot the bill themselves. In Gerber’s view, this is unjust, because not everyone with obesity has the means to pay out of pocket. He also finds it short-sighted: Weight loss injectables help prevent the development of secondary conditions such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes, thereby reducing the burden on the healthcare system. Swiss policymakers are currently discussing whether these injections should be completely removed from the list of treatments with mandatory health insurance coverage. “A decision of this kind would be completely wrong, from a medical perspective,” notes Gerber.

Fasting effectively

In Gerber’s research as a nutrition specialist, he deals not only with obesity issues but also with the general question of how to lose weight. That led him to conduct a study with a popular ongoing nutrition trend called intermittent fasting. People who adopt this way of eating divide their day into eating windows and fasting periods – an eight-hour eating window, for example, with sixteen hours of fasting. Another type of intermittent fasting is called alternate day fasting, which switches between normal eating days and fasting days that are low-carb or carb-free.

As popular as these methods are, there has been a lack of clarity about which methods are best. Gerber’s recently published study demonstrated that alternate day fasting was the most effective way to reduce body weight and total fat percentage. However, doing without food, or eating minimal amounts every second day, is akin to torture for many. He therefore wants to conduct a follow-up study to find out what and how much we can still eat within an alternate day framework while still losing weight. “Diets need to be both effective and feasible,” he says. “Otherwise they’re pointless.”

They should also be tailored to the individual: Diets don’t work the same for everyone due to differences in nutritional physiology. “That's why we need to treat obesity and excess weight in a more personalized way going forward,” says Gerber. One option is a portable breath analysis device developed by Alivion, an ETH spin-off that Gerber works with. Our breath can reveal when the body is burning fat and when we’re beginning to shed weight most efficiently. Alivion’s portable device can capture this exact moment. This would allow for diets and nutrition recommendations to be optimally tailored to individual physiology. “With wearables like these we can treat obesity with more targeted and effective means in the future,” says Gerber.

Policymakers must act

The research conducted by Lutz and Gerber is making an important contribution to solving the obesity epidemic. However, many of the children mentioned in the latest UNICEF report will not be able to benefit. To address the global obesity epidemic, UNICEF recommends policy measures against unhealthy ultra-processed foods and fast food – for example, clear labeling, advertising bans and bans on junk food at schools.