Germs and Kisses

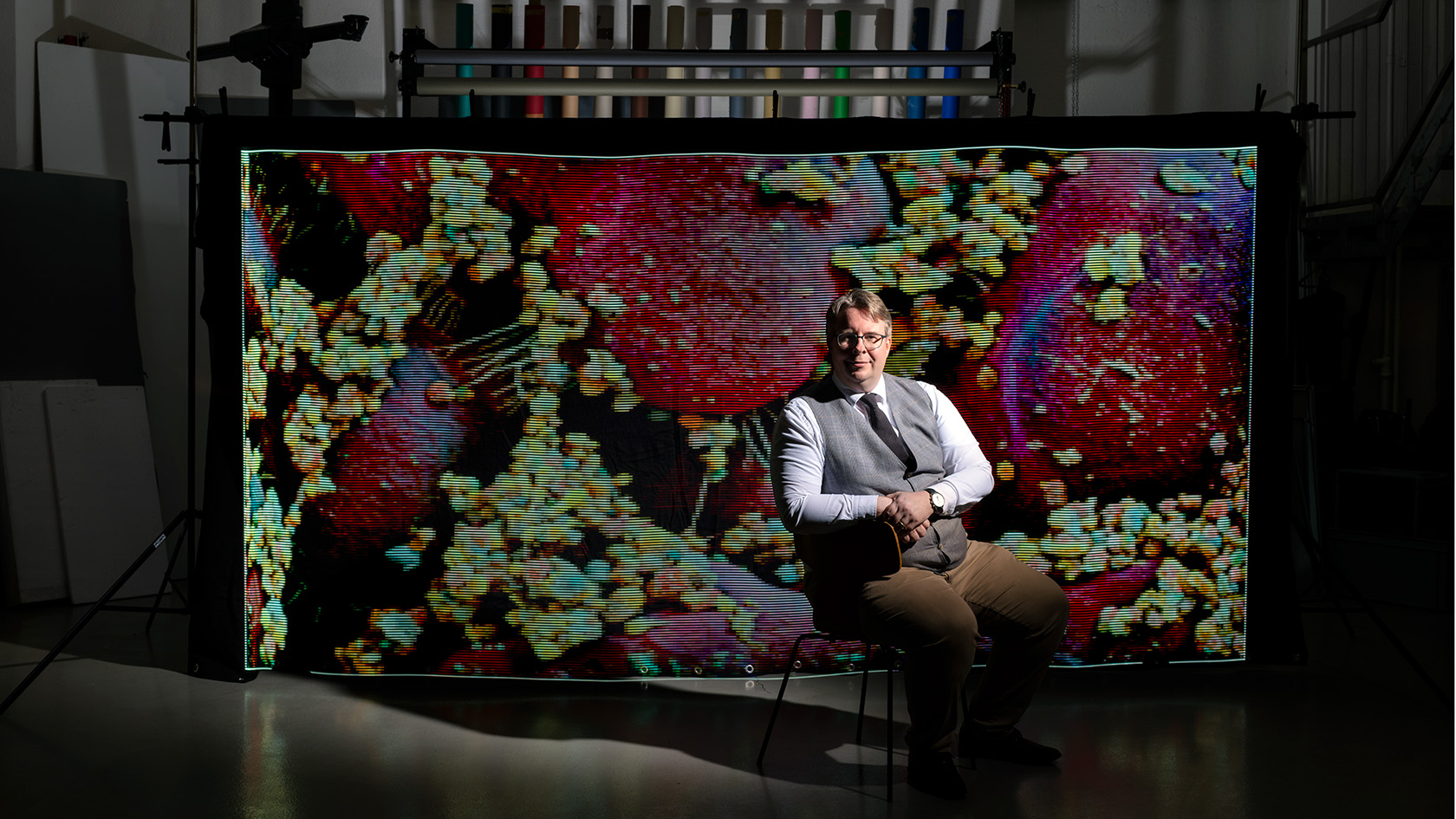

Adrian Egli gets straight to the point. When visiting him in his office, the first thing he does is stride purposefully toward a large photograph hanging in a prominent position in a corner. It shows hundreds of spherical and rod-shaped bacteria, in a variety of colors and magnified a thousandfold. “This is the microbiome of my wife’s kiss – it’s my favorite picture,” Egli says enthusiastically. The image, which was created with a scanning electron microscope, shows a small section of the amazing variety of microorganisms that colonize our lips. “The microbiome of one kiss on its own comprises 60 million bacteria,” explains the professor of medical microbiology. “In total, there are several billion germs lurking on our skin, and the gut actually contains a thousand billion, isn’t that fantastic,” says Egli – and each word he utters gives you a sense of how fascinated he is by these microscopically small companions.

The trillions of bacteria, fungi and viruses are critical to our survival; they help us digest food, support our metabolism and immune system, stimulate nerve cells and ensure our wellbeing. But microorganisms also have a dark and dangerous side, as they may cause dangerous diseases and can kill people in just days. As director of the Institute of Medical Microbiology, Egli explores this pathogenic aspect and works with his team to ensure that microbial infections can be diagnosed and treated as quickly and precisely as possible. The fact that this prolific researcher works in microbiology may seem perplexing at first. In the past, it had something of a reputation for being a serene scientific subject. This was because samples from patients usually had to be cultivated for several days before they could be placed under the microscope and identified with further tests. Thanks to technical advances in diagnostics – primarily ultrafast genome sequencing – this serenity is now a thing of the past. Nowadays, the genetic material from a bacterium can be sequenced down to the last component of its DNA in a matter of hours.

At the same time, high-tech methods like mass spectroscopy and more recently also AI methods have been available for characterizing the microorganisms that make people sick. Adrian Egli and his team are real experts in utilizing and developing these new technical possibilities. “I’m interested in finding quick and practical solutions,” says the scientist, who has both a medical doctor’s degree and a PhD in natural sciences.

A passion for microorganisms

Adrian Egli originally dreamed of a career as a scientist engaged in fundamental research in molecular biology. One of his mentors in Basel, where he studied around the turn of the century, inspired him to focus on medicine and infectious diseases. He studied medicine and submitted a scientific research paper on the BK polyomavirus that earned him his PhD title. “I developed a real passion for infectious microorganisms and laboratory medicine,” he says. The field is “incredibly wide-ranging and interesting” and enables him to utilize his aptitude for math and computer technologies. One example is the issue of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

In total, there are several billion germs lurking on our skin, and the gut actually contains a thousand billion, isn’t that fantastic?!

These dangerous pathogens are gaining ground all over the world, including in Switzerland. Several hundred people are dying in this country from infections caused by multi-resistant bacteria; around one million people are dying worldwide. This is why it’s so important to conduct rapid testing in the laboratory to find out which antibiotics will still work against a pathogen, because the time it takes to administer an effective treatment can be the difference between life and death.

Egli recently collaborated with colleagues from ETH Zurich to develop a novel method that combines mass spectrometry methods with artificial intelligence methods. The mass spectrometry produces a fingerprint of the bacterial protein molecules of a pathogen. AI that has been trained specifically on data from resistant bacteria is then able to detect on its own whether and which antibiotic resistances may be present in this new pathogen. This method is much faster than previous methods.

When Egli works on cross-disciplinary projects like this, his enthusiasm really helps him to persuade other people to embrace his ideas. “I like to look beyond my discipline and I really enjoy cooperating with different colleagues and fields,” he says. He’s also adopting this approach in another major research project focusing on virulence. This concept describes the ability of a microorganism to cause diseases – the more virulent a bacterium, the more dangerous it is. Astonishingly, virulence has hitherto been largely ignored in diagnostics, but it is vital for predicting the progression of a disease, says Egli. Working with his team and cooperation partners, he has now set about defining virulence factors such as the ability of a pathogen to penetrate into the tissue. AI should then be used to determine the correlation between the virulence factors and the courses of a disease using protein databases for the pathogens in various clinical centers abroad.

Born networker

With his work on virulence, Egli is exploring new areas of medical microbiology. “The field is currently undergoing great renewal,” he says with delight. The “tremendous opportunities” that Zurich provides for research were also one of the reasons why he decided to move from Basel to Zurich and take over as director of the institute in 2022.

As a born networker, he’s in his element in his new place of work. This spring, he invited thirty academic colleagues to attend the first “Pan-European conference on bacterial genome sequencing” in Engelberg. As was explained, the DNA sequence of a bacterium can be determined in a matter of hours, and this multiplies the number of diagnostic options available. This makes it possible, for example, to map the incidence of infection and the formation of any resistance with unprecedented precision, provided the genome data is exchanged as widely as possible. The big topic at the conference was how this cooperation can be accelerated at a European level.

Egli initiated this gathering following the experiences he had with Covid-19. “The pandemic showed us how important it is to have the genome data for pathogens,” says the microbiologist. At the time, Egli was also at the forefront of efforts to systematically provide the sequence data for Sars-CoV-2 in Switzerland. As a consequence, the SPSP (Swiss Pathogen Surveillance Platform) database was set up and is now available for all laboratories and the FOPH to access.

Adrian Egli sings its praises. “This database is a successful model and is constantly being expanded for new pathogens,” he says with delight, explaining the new opportunities for personalized medicine. And then you’re also struck by another quality: his ability to communicate. His persuasive and charming demeanor makes Egli a natural orator – a skill that he also puts to good use in explaining the world of microbes to a wider audience. For example, he’s involved in a citizen-science project with students from Wattwil in which samples are collected from the oral flora, and he gives talks to the Children’s University at UZH. He is also very happy to make time for exceptional projects: for example, he worked with high school students to organize a seminar on infectious diseases in literature and explained the medical background to the “Ballad of Typhoid Mary” by Jürg Federspiel. And when medical students ask if he fancies a party, he’s always happy to say yes.