A Smartwatch App to Tackle Long Covid

André Meyer-Baron and Carlo Cervia-Hasler met about a year ago at a networking event organized by the Digitalization Initiative of the Zurich Higher Education Institutions (DIZH). As they spoke, they quickly realized that their scientific backgrounds and interests were an ideal match.

André Meyer-Baron’s research at the Department of Informatics focuses on approaches to improve the productivity of knowledge workers. Among other things, he has developed a digital platform that helps teams find a better balance between focused work and teamwork. Carlo Cervia-Hasler from the Department of Immunology at the University Hospital Zurich, meanwhile, conducts research on biomarkers that can detect Long Covid in the blood. The trained physician and scientist has developed a score that can be used to assess a patient’s individual risk of developing Long Covid.

Interdisciplinary cooperation

“I wanted to ask Carlo for some advice for a friend of mine who had Long Covid,” remembers Meyer-Baron. This initial exchange evolved into a promising cross-disciplinary project that ultimately brought about a digital platform aimed at Long Covid patients. The researchers’ work has now won them the 2023 UZH Postdoc Team Award.

How to avoid excessive exertion

It is estimated that around 200,000 people in Switzerland suffer from Long Covid, and there is still no medication to treat the disease. This is why many patients are currently using a strategy known as pacing to manage their symptoms. The strategy involves patients carefully planning and managing – or pacing – their physical activities to avoid overexertion and “crashes”. For example, they record how many hours they sleep, they measure their body temperature or write down their symptoms and physical activities in an activity diary. However, keeping track of all these things by hand is very difficult when you’re suffering from fatigue, joint pain or brain fog – all of which are common symptoms experienced by Long Covid patients.

No effective digital tools

“There are currently no digital tools that provide patients with effective support for activity pacing, even though sensors that could provide important data for this already exist,” says Meyer-Baron, who has also researched the use of biometric sensors. Smartwatches, for example, can be used to monitor a person’s physical activity and health-related data. “However, current applications are geared toward increasing a person’s activity,” says Cervia-Hasler. The two researchers therefore decided to develop their own application.

Setting limits

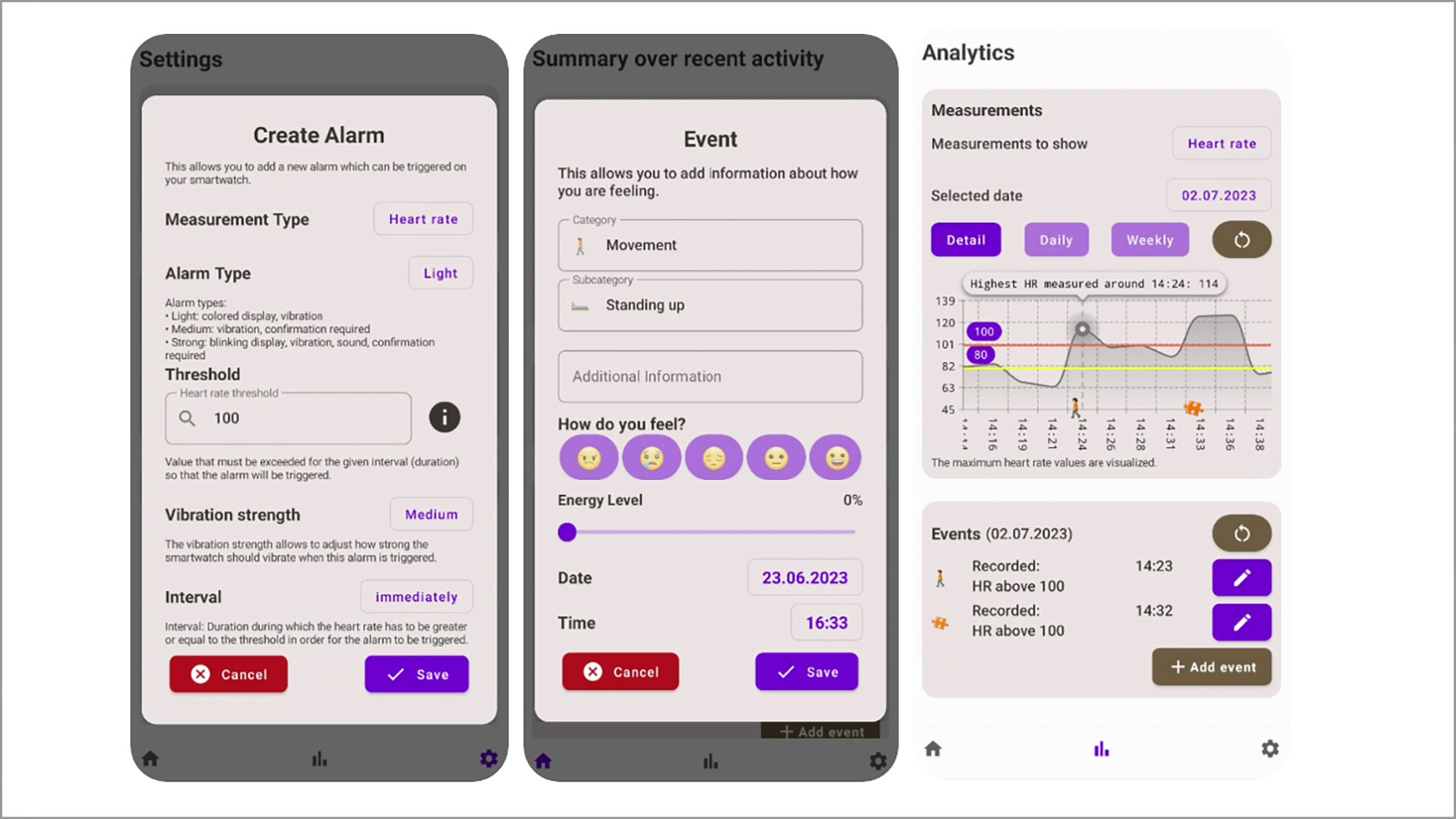

The innovative digital platform, which the researchers dubbed MindfulPacer, includes a smartwatch application as well as a smartphone app. The smartwatch monitors the patients’ heart rate and step count, providing feedback in real time, while the app provides an intuitive visualization of their biometric data. Patients can then use this information to set individual limits for their heart rate or daily step count, for example. These limits are linked to a warning system that alerts patients through the display of the smartwatch. A green display means that values are normal, whereas orange or red indicates that the limits set by the user are about to be reached or have already been exceeded. If this happens, the smartwatch will vibrate and sound an alarm. In addition, users are prompted to make a note of what caused the alarm as well as how they are feeling in the app.

Improved symptom awareness

This alarm function helps users to reflect on their activities and improve awareness of their symptoms. Integrating a patient’s individual data into the visualization enables them to better understand where their limits are and adjust them accordingly. “MindfulPacer makes it easier for people with Long Covid to recognize patterns in their heart rate and step count, which helps them regulate their daily physical activity. This empowers them to manage their disease,” says Cervia-Hasler. “MindfulPacer is a simple tool that helps patients help themselves,” adds Meyer-Baron.

Cooperation with Swiss patient organization

At present, MindfulPacer is still a prototype, and only a handful of Long Covid sufferers are currently using it. The UZH researchers are using their feedback to continuously improve the digital platform. They also worked hand in hand with the Long Covid Switzerland patient organization to tailor the platform to the specific needs of patients. “Their feedback was extremely helpful,” emphasizes Meyer-Baron.

Immediate benefits

The user-oriented and iterative development of digital applications is part and parcel of Meyer-Baron’s work in his field, whereas his colleague was unfamiliar with the approach. “I normally work with large amounts of patient data. It was very enriching to focus on the perspective of a few people for a change and continuously integrate their feedback,” says Cervia-Hasler. Both scientists agree, however, that learning from each other has yielded excellent results. “We’re very happy that we were able to develop something that has immediate benefits for patients.”

Rolling out the platform

The feedback from current test users has been consistently positive. This has reinforced the researchers’ decision to make MindfulPacer available to a wider audience. Once they receive ethical approval, the scientists want to carry out an in-depth assessment of the user-friendliness and effectiveness of their platform. At the same time, they plan to make a first test version available to the public. In collaboration with Long Covid Switzerland, the researchers are also working on adding an online forum that will enable users to share their experiences.

To fund these next steps, they have applied for an Outreach Call at DIZH. However, there are no plans to market their platform. “Our main goal is to help as many people affected by Long Covid as possible and to work together with them to keep advancing MindfulPacer,” says Meyer-Baron.