Equipping Children for Life

Research Spotlight: Developmental Psychology (Video: MELS, UZH)

What do children need to grow up happy? Moritz Daum’s answer to this big question is short and sweet: a shovel and chocolate. The shovel symbolizes learning through play and the motor and cognitive tools that children need to acquire to find their way in life, to understand the world and to express their feelings. It also includes the skills needed to self-regulate and to be attentive without being constantly distracted.

Meanwhile, the chocolate represents the positive emotions that are important for children to grow up happy. When we eat chocolate, our bodies release endorphins, or feelgood hormones. “Figuratively speaking, this means that children need emotional security,” says Moritz Daum, “they should grow up surrounded by positive relationships built on mutual trust.” Equipping children with a backpack full of confidence and resilience in childhood is a good basis for a positive journey through life.

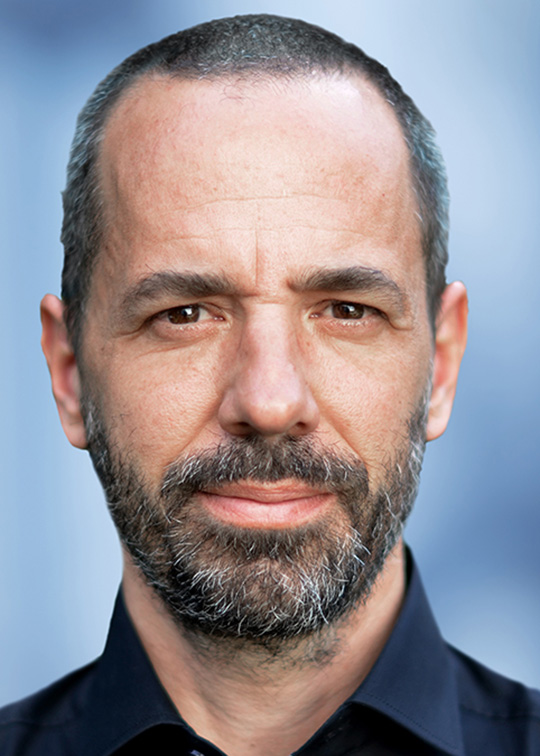

Moritz Daum researches how children develop and how they can best fulfill their potential at the Department of Psychology and at UZH’s Jacobs Center for Productive Youth Development, of which he is director. He also co-authored the book Kindheit. Eine Beruhigung, which was released last spring and quickly made it onto news magazine Der Spiegel’s non-fiction bestseller list. The book is aimed at a broad audience. It was written by a collective of authors, including UZH researchers from a wide range of disciplines.

Developmental psychologist Daum noticed that parents are hungry for information and that there is a great deal of uncertainty. After giving presentations on child development, which he does regularly, he always gets asked the same anxious questions: what’s the right parenting style? How much freedom does my child need? And how much encouragement?

The book Kindheit. Eine Beruhigung answers these and many other questions from a science-backed perspective. It also dedicates two chapters to what makes children happy and what makes good parents. There is no universal formula for this, however. “Our aim was not to write a finger-wagging self-help book, but to get people to think about what makes a good childhood,” says Moritz Daum. The book aims to reassure parents and encourage them to relax a bit.

Children need emotional security, they should grow up surrounded by positive relationships built on mutual trust.

This is because their influence on their child’s development – although it should not be underestimated – is not as significant as they sometimes assume. Children are intrinsically motivated and innately inquisitive – they do a lot of their own accord. Studies have shown that parents only contribute about 50% to their children’s success in life, the other 50% is down to their genes. “Parents can’t control or decide their children’s life paths,” says developmental pediatrician Oskar Jenni.

And they shouldn’t feel responsible for everything either. “For example, it’s not their responsibility to plow through lessons with their kids – that’s the school’s job,” says Jenni, “parents primarily need to be emotionally present.” In other words, they are mainly responsible for the “chocolate part” of child development. Having a positive and trusted relationship with their parents is crucial for a child, particularly if they have a developmental disorder such as ADHD or dyslexia and therefore struggle at school. Oskar Jenni knows this from his clinical practice.

The developmental pediatrician initiated the book Kindheit. Eine Beruhigung and focuses on healthy childhoods and on problems and disorders in child development in his work as a researcher and physician at the University Children’s Hospital Zurich. To grow up healthy, children’s basic needs must first be met, says Jenni. Children need to be well fed and given the chance to be physically healthy; they need loving caregivers, the opportunity to experience, learn, and make mistakes through free play, but they also need structure and guidance, and to live and grow up in stable societies. “In war-torn regions, like the Middle East and Ukraine currently, children can’t grow up happy,” says Oskar Jenni.

The “five Vs”

The developmental pediatrician is clear that experiencing positive and trusted relationships in childhood is essential to quality of life and happiness in later life. He maintains that they are even more important than intelligence and education. Another prerequisite for the child’s wellbeing is the quality of the parents’ relationship. For example, partners should not only talk about the logistics of everyday life – such as who is picking the child up from nursery and who is cooking dinner – but also about their own ideas, wishes and dreams. As Jenni explains, it’s extremely important – both for couples and for children – that parents look after their own wellbeing, too.

The importance of the relationship between a child and their parents to subsequent life paths has also been shown by the Zurich Longitudinal Studies, which Jenni leads. Researchers at the ZLS have been documenting and analyzing human development, from childhood to old age, since 1954, and are currently collaborating with the UZH-associated Marie Meierhofer Institute for the Child.

In one study, scientists from the institute compared the life courses of people who grew up in one of Zurich’s children’s homes in the 1950s, with those in the ZLS who grew up in a family setting. While the children brought up in an institution were physically cared for, they experienced less emotional support than the children in the control group. This had far-reaching consequences. The children had worse life outcomes on average: they were less happy, were more likely to suffer from mental health problems, and died younger than the children who grew up in families.

Parents can’t control or decide their children’s life paths.

The institutionalized children were lacking one or more of what Oskar Jenni refers to as the “five Vs” (as they all begin with V in German) – five essential factors that cover children’s emotional and social needs and give them self-confidence. According to these “five Vs”, parents, grandparents and other important people in a child’s life should be trusted, reliable, available, understanding and loving (or in German, vertraut, verlässlich, verfügbar, verständnisvoll und voller Liebe). “They should be present, interested in the child, and predictable in their actions – this makes the child feel safe and secure,” says Jenni.

They should also be understanding; in other words, they should try to recognize and understand the child’s individual needs and abilities and respond appropriately. This also means that they need to reconcile their own ideas and expectations with their child’s character and abilities. “For example, not every child is intellectually gifted and will take the academic route,” says Oskar Jenni “instead they might have creative or social strengths.”

Climbing frames and scaffolding

The fact is that children develop very differently by nature – there is no hard and fast rule. This has been clearly shown by the ZLS in recent decades. Children are happy and content if their own abilities and needs match the requirements placed on them. In other words, when there’s a fit between the child and their environment, as Remo Largo, Oskar Jenni’s predecessor, called it.

Research has also clearly shown that children develop best when they are supported and supervised on tasks that they cannot yet solve on their own, but are given freedom in areas where they are already proficient. “Take the example of a three-year-old who wants to reach the top of a climbing frame,” says Oskar Jenni. Whether the child makes it to the top or not depends on their individual abilities. While some will barely make it past the first rung, others will scramble effortlessly to the summit.

“Even if they’re not sure whether their child will manage to climb to the top or lose their balance on the way up, parents should try not to worry and not to be overly protective,” says Oskar Jenni, “instead, they should let the child try on their own, but be there to help if they get into trouble.” In psychology the term for this is scaffolding, which is important to positive development. Parents should be like a scaffold for their children. “They should provide support and guidance, but also give them enough freedom and not rein them in too much, so that they can grow and thrive,” says Moritz Daum.

Freedom and control

Consistently striking this balance between freedom and control is an art that parents can practice throughout their children’s development. When the children are young, this might be about what they’re allowed to go on at the playground, and later when they’re teenagers, it might be whether they’re allowed to go out, how long for, and where to. If the balancing act is successful, it builds self-confidence and self-esteem, which are important resources for later life.

“I firmly believe that an upbringing based on trust makes children and young people more resilient than a rigid and authoritarian parenting style,” says Moritz Daum. Too much control has a negative impact in the long run, particularly in teenagers. “It disempowers young people, erodes their self-esteem, and impacts their wellbeing,” says Oskar Jenni. But too little control is not good either.

From building a scaffold to walking the tightrope between freedom and control – being a parent isn’t easy. “But they don’t have to be perfect – good enough is enough,” says Moritz Daum. The idea of good enough parenting was developed by English pediatrician and psychoanalyst, Donald Winnicott. “Good enough means that parents should be there for their children and give them stability, but they should also make it clear where their boundaries are,” says Moritz Daum. And although parents are the main role models for their children, they are allowed to make mistakes sometimes, too. This is reassuring for parents and takes the pressure off children, because it teaches them that – luckily – no one has to be perfect.