Trump’s Wrecking Ball

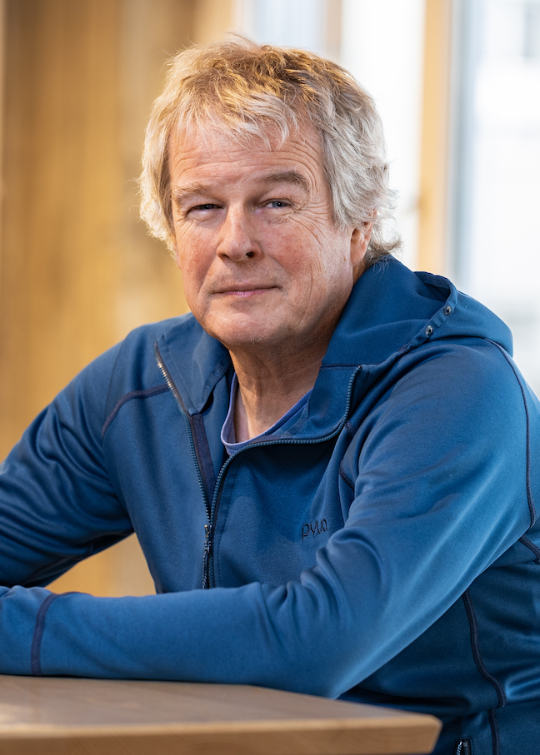

US President Donald Trump believes that the United States is being economically exploited by other countries, as evidenced by US trade deficits with many of these nations. He wants to fix this by imposing high tariffs, which he hopes will strengthen the US economy, boost domestic manufacturing and create jobs. However, Trump’s policies containmany elements that can weaken the economy and trigger or worsen an economic crisis. His administration’s current policies offer a good opportunity to examine what makes an economy resilient and crisis-proof – or conversely, what weakens it and makes it vulnerable to crises. A five-part analysis by UZH economists Thorsten Hens, Steven Ongena and Ralph Ossa.

1. Trust and stable institutions

What’s good for the economy: Trust and stable institutions create security for investment and planning.

What the US is doing: Undermining trust in themselves, in their global leadership role and in international organizations like the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank and the WTO.

Trust acts as an essential glue and lubricant – for interpersonal relationships as well as socially and economically. The Trump administration has already destroyed a great deal of this trust through erratic behavior such as imposingarbitrary tariffs. Financial markets – in their role as important, incorruptible trust indicators for the economy and the government’s economic policy – have already reacted, says Thorsten Hens, professor of economics at UZH: “US stock prices have been adjusted downward, the dollar has lost value against the Swiss franc, and a lot of money has flowed out of the United States to other countries.” He predicts that this money won’t return anytime soon, as trust in the US government has evaporated: “And as we know, trust is destroyed much faster than it can be built.”

Another reason for the loss of trust in the US is the country’s unwillingness to continue taking on a global leadership role and to bear the associated costs. “The US was essential. They created an empire based on its constituent parts benefitting from certain services the US provided – like European countries or NATO members,” says UZH economics professor Steven Ongena. “Now the United States is retreating from this role. That’s a shock. And we’re only at the beginning of this development.”

The US withdrawal from its role as hegemon is devastating because trust in American leadership and reliability was essential for stabilizing global trade and finance. “Trust is what makes these systems resilient,” Ongena explains. This especially holds true for the global financial system, the fragility of which was exposed by the 2007-2008 crisis. In response, coordinated regulations were enacted worldwide that led to improvements such as better capitalized banks. This approach worked fairly well during the Covid pandemic, Ongena says, noting that the global financial system passed that particular stress test.

Trust in major central banks and the European Central Bank plays a crucial role. They are supposed to intervene during emergencies, and this has indeed been the case historically. But can we count on the largest central bank – the American Federal Reserve (Fed) – to step in during future crises? “We don’t know,” says Steven Ongena. The Fed is under massive pressure from the Trump administration to make certain decisions, such as cutting interest rates. For now, Fed Chair Jerome Powell is resisting this pressure, but Trump can replace him with a presumably more compliant person by next year at the latest. Such a move would further undermine trust in the Fed.

The same applies to the IMF, the World Bank and the WTO, where the US plays an important role. If the US no longer cooperates or starts to push back, these organizations lose significance and influence. “This is very problematic,” says Ongena, “because what we actually need is global leadership and governance of financial markets and global trade.” Currently, this seems even less likely than it did before.

2. Open markets and international trade

What’s good for the economy: Global trade and competition create incentives for companies to offer good, affordable products.

What the US is doing: Protecting its economy with high tariffs, which weakens competition and makes products more expensive for American consumers.

To find something comparable to the global trade war recently kicked off by the US, you have to go back to 1930. In that year, the US passed the Smoot-Hawley tariff act, named after the two congressmen who initiated it, Reed Smoot and Willis C. Hawley. The act raised tariffs to record levels on more than 20,000 products. The goal was to protect the US economy from foreign competition.

The act was as successful as it was devastating. By 1933, imports to the US had dropped by 66 percent, and exports fell by 61 percent over the same period. Because the law led to retaliatory tariffs and other protectionist measures in other countries, world trade declined by 60 percent, worsening the Great Depression.

“The trade war in the 1930s was on a different scale than today because the current trade war only affects trade relations with the US,” says Ralph Ossa, a UZH economics professor who served as chief economist of the World Trade Organization (WTO) until the end of June. In 2014, Ossa published a trade war simulation study: “Back then, people told me that it was an interesting paper but trade wars like that wouldn’t happen anymore because we’ve learned from the crisis of the 1930s.” It was also seen as unrealistic that a trade war could lead to tariffs of 30 to 60 percent, as Ossa had modeled. “I thought that was high myself,” he says. “But now we’re happy when tariffs are only 15 percent like for the EU and not 39 percent like for Switzerland. It’s really unbelievable.”

We live in a risky world where we cannot necessarily rely on individual trading partners. That is why it is important to have several options. Diversification is always a good response to risk. This also applies to trade.

These tariffs end up making products more expensive for American consumers; many products will probably endup not being imported at all anymore due to high costs. Onega believes that Trump’s tariffs and the associated supply chain problems and rising costs will slow down the US economy. Tariffs and other trade barriers are poisonous for economies, he says, and will likely cause the otherwise robust American economy to slip into a recession. A global recession could also be on the horizon.

For Ossa, the antidote is what makes economies resilient against crises: open, multilateral trade, which is also championed by the WTO. This was put to the test by Covid. “In Switzerland, we only coped with the pandemic so well because we could get the products we urgently needed – like masks and ventilators, and then vaccines – from the global market,” says Ossa, noting that it’s important to have a broad, well-diversified network of trading partners. “We live in a risky world where we can’t necessarily rely on individual trading partners. That’s why it’s important to have several options. Diversification is always a good response to risks, and that applies to trade too.”

3. Flexibility and dynamism

What’s good for the economy: An economy should be dynamic and capable of quickly adapting to new circumstances, provided that the regulatory environment allows it to do so and that there’s a sufficient level of competition.

What the US is doing: Pursuing an outdated economic policy with protectionist measures aimed at reviving obsolete industries.

According to UZH economist Thorsten Hens, protectionist measures like high tariffs will hurt rather than help the American economy: “The Trump administration is trying to turn back the clock and re-industrialize the country. It’sa dead end.” Producing more steel and coal in the US again doesn’t make sense, Hens says: “The US should look forward and focus on innovation. They’re already very strong in a lot of sectors.” Relying on the flexibility of the economy is a better move than mourning the past: “It’s a system capable of evolving, and it can adapt to new circumstances.” Hens points out that this is also happening during the current trade war, with China and Europe – Switzerland included – needing to identify new markets for their products or having to find ways to produce and export their products to the US while keeping tariffs as low as possible. Financial markets have already reacted by reshuffling portfolios – fewer US stocks and more investment in other countries.

“Being resilient means being flexible, like reeds that bend during a storm and then stand up again when it’s over,” says Hens. The opposite of this is the sturdy oak, which may be robust but topples over when the storm gets too strong. Hens advises that during a crisis, one shouldn’t try to cling to or bring back what used to work, which is what the current administration is trying to do. Rather, the key is to “master structural change.”

Switzerland has done this well over the past decades. Although the country has lost large parts of its traditional industry, it still boasts near full employment and a dynamic, innovative economy. Hens sees a major opportunity for Switzerland in the blockchain industry, where it’s a leader. And more high-caliber scientists will come from the US to Europe, which should boost innovation.

4. Low debt creates financial flexibility

What’s good for the economy: Countries with low debt burdens have greater leeway to provide short-term economic support during emergencies like a pandemic.

What the US is doing: Trump’s Big Beautiful Bill will further bloat US debt levels.

Save up for a rainy day, as the expression goes. This doesn’t just hold true for people or companies, but also for countries. Yet governments typically ignore this advice, as the US has once again demonstrated by reducing taxes for the rich and ballooning their massive national debt even further.

“Will the US go bankrupt soon?” UZH economist Thorsten Hens asked this question in a June presentation for an asset management firm. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent had just assured the public that this would never happen: “The United States of America will never default.” Bessent was trying to bring calm to the markets after the rating agency Moody’s had downgraded US government debt, and yields on long-term government bonds had risen sharply. Rising yields on bonds means the government has to offer higher interest rates when issuing new bonds, which makes servicing the national debt more expensive.

This is precisely the scenario facing the US this year. “They need to refinance a third of their national debt,” says Hens, referring to a third of the $36 trillion that are owed. On top of that comes an additional $4.1 trillion from the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (also called the Big Beautiful Bill), the sweeping piece of legislation that Donald Trump signed on 4 July. This “beautiful” bill is notable for its tax breaks for the wealthy and will see US government debt jump from 124 to 137 percent of GDP. To put this in perspective, Greece’s debt ratio is 158 percent and the EU’s is just over 81 percent, while Switzerland sits at 38 percent.

In the future, the US will have to spend even more to service its debt. This money will then be lacking elsewhere, for example in education, health, and social services.

“The US will have to spend even more on servicing its debt in the future,” says Hens. “This money will then be lacking elsewhere, for example in education, health, and social services. The Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), which was initiated by Elon Musk, has already made cuts in these areas.

Tariff revenues, which put just a few billion into government coffers, would only be a drop in the bucket when it comes to paying off the massive debt burden. In the end, US national debt remains far too high. Government debt spiked in many countries during the pandemic, and while some of it has been paid off, it is still higher than pre-Covid levels. “When the next crisis hits, governments will have less flexibility to soften the blow,” says Hens.

5. A strong education and social welfare system

What’s good for the economy: Strong education and social welfare systems help cushion the impacts of structural change and promote social mobility and innovation.

What the US is doing: Shrinking their social welfare and education systems; moreover, higher education is unaffordable for many, making structural change and social mobility more difficult.

Steven Ongena finds it incredible that US government policies are hurting many people who voted for Trump: “Trump promised to solve their problems, but he’s only making them worse.” The education system is one of the country’sproblem areas: higher education has become largely unaffordable, with many having to take on debt that burdens them for the rest of their lives. Instead of making education more accessible, Trump is cutting university funding and slashing the Department of Education’s budget to the point of collapse. He would prefer to eliminate it entirely, but this is a move for which he would need congressional approval.

Trump promised to solve the problems, but he is only making them worse.

According to Ongena, the fundamental problem in the US is that the rich are no longer willing to finance the education system, as they can afford to send their children to private schools; Trump’s cuts are an extreme expression of this attitude. As a result, he says, public schools are often cash-strapped and perform poorly, cutting off many Americans from pathways to social mobility. For those who are already well-off, this isn’t a problem because they can defend their advantages and privileges this way. “Wealthy individuals and families will fight by any means to prevent others from becoming rich too,” says Ongena. This means shutting others out of the education system.

For those who can afford good private schools, this calculation might work out, but not for society as a whole. As studies by Ongena and his colleagues show, excluding a large portion of the population from education means fewer people are willing and able to become entrepreneurs. “This makes the economy less dynamic and innovative,” says Ongena. “What’s crazy is that we know from research what it would take. Yet they’re doing exactly the opposite in the US right now.”

Things are different in Europe, where education remains accessible and affordable in most countries. UZH economist Thorsten Hens uses himself as an example: “I come from the Ruhr area, a coal- and steel-producing region. When structural change hit this sector, my father’s generation became unemployed in their late fifties and early sixties. But we as the next generation could go to university with a federal scholarship, the BAföG.”

There’s no comparable support system in the US to soften the blow of structural change and give workers in declining industries new prospects.

The current administration in the US lacks the will to change this. Going forward, there will also be a dearth of funding – something Trump has ensured with his tax cuts. Taxes are the tool for achieving greater social equality. “That’s why taxation is the key question for addressing the problems facing America’s middle class,” says Ongena. After all, only a government with sufficient financial resources can fund an education and social welfare system that provides real educational and life opportunities to large segments of the population. This creates the foundation for a dynamic and innovative economy.