Less Stress, Better Research

According to Swiss law, before new substances can be trialled on humans, they must first be tested on animals. Because the majority of therapeutic compounds are intended to be taken by mouth, they are also administered to mice and rats orally in the testing phase. How does it usually work?

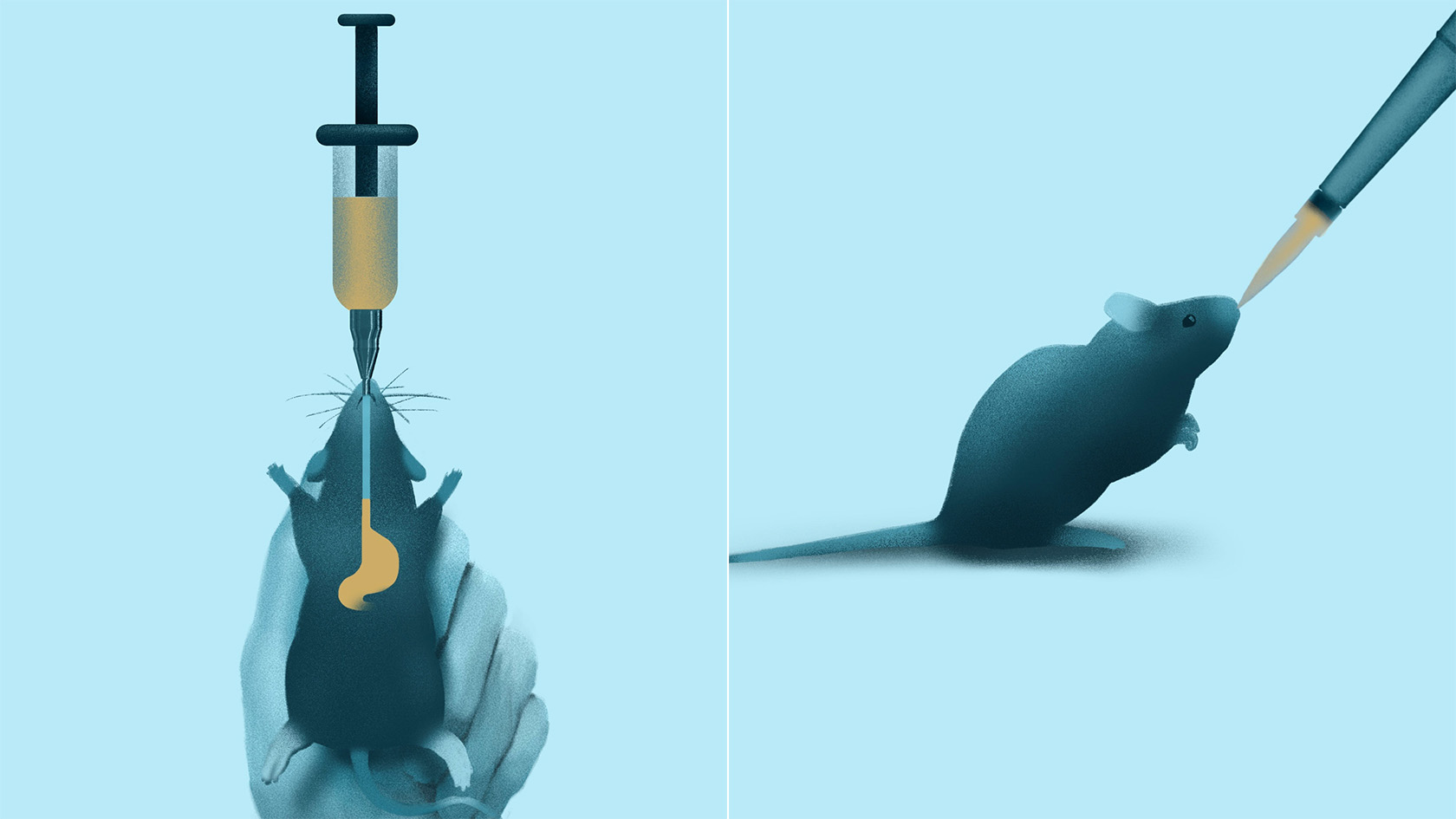

Urs Meyer: By far the most commonly used method to orally administer substances to rodents is called oral gavage. With this method, the substance is administered via a tube inserted into the animal’s oral cavity and down into the stomach. To do this, the researcher needs to keep tight ahold of the animal’s neck, which is a tricky business if the animal doesn’t want to ingest the unknown substance, for example because it tastes bad.

So the ingesting of the substance by the animal is a completely involuntary process?

Yes, that’s right. The key point for the researchers is that this method enables them to control the dosage and timing. It is also possible to give a substance via drinking water or food, which is obviously less stressful for the animals. But the problem is that the researchers then do not know exactly how much the animal ingested and when.

What are the center’s aims?

The current method entails a high degree of stress for the mice. The animals are not anesthetized, so they are awake during the procedure. In addition, inserting the tube can lead to irritation or damage to the oesophagal tissue or the stomach, especially if the researcher carrying out the procedure is relatively inexperienced. The method can also be stressful for the researchers. They know that the mouse is stressed, and may worry about injuring it.

Some time ago, your team developed a gentler method of orally administering substances to laboratory mice. How did this development come about?

It was scientifically necessary for us to come up with an alternative. We do basic research into brain development disorders such as autism and schizophrenia. Mice are used to study how environmental influences disturb brain development, and how this affects the mice’s behavior later on. Together with several pharmaceutical companies, we also test new treatments using animal models.

Around four years ago, we had to orally administer a substance to young animals daily over three months. We began with mice that were only three to four weeks old. The smaller a mouse is, the more difficult it is to perform the standard procedure. We knew we couldn’t carry out the experiment in that way as stress, particularly chronic stress, influences mice’s behavior. Regularly administering the substance via oral gavage would have obscured our findings. We therefore needed to find a way that was as stress-free as possible.

What did you do?

We knew from behavioral experiments that it is relatively easy to train mice to ingest substances that taste good – such as diluted condensed milk. They like the taste, and drink it voluntarily without a lot of training. We offered the mice the diluted condensed milk using a conventional micropipette, and after a short period of time and minimal training, they drank it voluntarily. We thought “wow, this is it!” The method is called “Micropipette-Guided Drug Administration”, MDA for short.

We offered the mice the diluted condensed milk using a conventional micropipette, and after a short period of time and minimal training, they drank it voluntarily. We thought “wow, this is it!”

How do you accustom the mice to drinking from a pipette in the lab?

We start in the same way, by holding the mouse by its neck. On the first day, while the mouse is restrained in this way the pipette tip is brought to its mouth – the mouse sees the substance and drinks it. On the second day, it is enough to place the mouse on the cage and just hold it by the tail so that it drinks from the pipette. And by the third day, the mouse drinks voluntarily without being held.

Because mice are incapable of vomiting, they are very cautious about new substances. They try a tiny amount at first and then wait to see what happens. If nothing happens after about two hours and the new substance is palatable, they quickly lose their initial reluctance. The sugar activates their reward center, which is why only two days of training are necessary.

What are the advantages of the new method?

We developed the MDA method primarily to administer substances which have to be given regularly over period of time. It means much less stress for the mice, as they no longer need to be restrained or have a gavage. This also eliminates the risk of potential tissue damage. In our tests, we were able to give the mice a substance daily for up to four months during which time none of the animals had to be removed from the experiment. Another advantage is that condensed milk is cheaply available.

How do you know that the test animals experience less stress and have higher well-being?

There are many ways of monitoring how an animal is faring, and according to the Animal Welfare Act we are obliged to do so. Certain signs of stress can be spotted visually, for example when an animal loses weight, stops grooming, reduces its activity or withdraws. Stress can also be determined physiologically by measuring the amount of stress hormones – such as corticosterone or noradrenaline – an animal releases in an experiment. In this area we measured massive differences between the MDA method and the gavage.

According to your publications, you also obtain qualitatively better and more reliable research findings with the new method. Why is that?

First of all let me stress that we are not saying that all research findings obtained to date with the gavage method are bad. But there are research questions for which the MDA method is better suited and results in better quality findings compared to the standard method, especially in behavioral tests. A stressed animal is in defense mode and has no desire to do or learn anything new.

With MDA, the negative effects of stress are not present during physical activities and cognitive tests. Our results clearly show that the animals in experiments using the MDA method are much more active and eager to explore, unlike stressed animals which withdraw and wait. Stress can therefore conceal certain behavioral patterns or, in the case of sedatives for example, reinforce them.

The method was first published in 2020. Your PhD student at the time, Joseph Scarborough, played a decisive role in the development and was awarded the Young 3Rs Investigator Award by the Swiss 3R Competence Center (3RCC).

We were naturally delighted that MDA was so well received in research circles. Many research groups, primarily from UZH, approached us to find out more about the new method and are now using it. Young researchers in particular are very interested – many of them hate using the gavage method.

So were all the reactions positive?

Yes, and not just around the scientific publication. A number of research teams who were experimenting with similar methods but had not yet made as much progress as us also posted messages on social media such as X (formerly Twitter). Within UZH, the staff of the Office for Animal Welfare and 3R in particular helped us disseminate the method. They are in touch with many researchers and know which teams are planning relevant experiments. When researchers apply for authorization for an animal experiment, the animal welfare advisers recommend that they try out the new method.

The National Research Programme 79 “Advancing 3R” of the Swiss National Science Foundation has made almost one million Swiss francs available to implement MDA. What are your aims within the NRP 79?

Researchers usually rely on tried and tested methods in their work, so the question is: how do we motivate them to try something new? The answer: with data. One aim is to examine MDA from as many angles as possible in comparison with the standard method, particularly with regard to pharmacokinetics and metabolism. We want to know where it does and doesn’t work. How is a substance distributed in the body? Do the sugars and fats in the diluted condensed milk have undesirable effects? We also want to test alternatives, such as liquids containing sweeteners instead of sugar. We – that is, Pal Johansen’s group at the University Hospital Zurich and my team – want to generate data on all these aspects and make it available to the scientific community.

Where does MDA meet its limits?

One example is with very bitter substances that an animal would never drink voluntarily, even if they are dissolved in a sweetened liquid. However, of all the substances we have tested so far, this has only happened once. Detailed research into metabolic processes also poses a challenge for this method, as each individual ingredient of the condensed milk can influence the measurements. However, I am convinced that the gavage can be replaced by MDA in many areas of research.

What hurdles need to be overcome to ensure that MDA is used as widely as possible?

Paulin Jirkof, 3R coordinator in the Office of Animal Welfare and 3R, is focussed on this task. She uses networks within UZH to spread the message, and at a national level the networks of the 3RCC. Internationally, she makes the method known to a wide audience via the Federation of European Laboratory Animal Science Associations (FELASA). She also organizes seminars and creates videos and training material. In the courses in laboratory animal science organized by Zurich institutions for students and scientists conducting research with animals, MDA is already presented in detail in the theory section. This is very important for its dissemination, as the courses are compulsory.

Another focus is on authorities and political decision-makers, such as the cantonal veterinary offices and the federal parliament.

What else is needed?

MDA can already be used for many research objectives. One big exception is analgesia. We do not yet have any data showing that a painkiller has the same concentration in the blood or brain and works the same whether it is injected, administered by gavage or by MDA. We plan to obtain more data and close this gap. As soon as the data are published, we will contact the veterinary office with the aim of getting MDA approved for pain relief.

Do you think that MDA will become the standard method for the oral administration of substances in animal research in the future?

Well, that’s our long-term goal. MDA should become the legally recognized standard method for oral applications. The gavage procedure should only be allowed as an alternative in cases where MDA does not work. At the moment, it is still the other way around, but the potential offered by a virtually stress-free oral substance administration method is huge. This is precisely why it is crucial that 3R research is supported financially, and I am very grateful to the SNSF for this. After all, developing methods that refine, reduce or replace animal testing costs money, and it’s important that we continue to improve in these areas in the future.