Students Help Shed Light on Prehistoric Marine Giants

It was an aquatic predator that grew up to 20 meters long and had teeth the size of a human hand. And it was absolutely lethal. These words describe the mighty megalodon (Otodus megalodon), the largest shark that ever lived. The prehistoric predator went extinct some three million years ago, but its closest living relative, the great white shark, still rules the waters. However, at up to seven meters, even the great white pales in comparison to its massive ancestor.

The megalodon is one of many extinct species that once roamed the seas – and about which scientists have already learned a great deal. And yet, extinct marine megafauna has never been assessed as a whole, nor has it been defined. This is what UZH professor of paleontology Catalina Pimiento set out to do in a paper, for which she involved students from her block course Marine megafauna in deep time.

A new definition

Defining extinct marine megafauna isn’t as easy as it may sound. Until recently, the definition leaned heavily on how today’s marine megafauna is defined, i.e. any species that weighs more than 45kg and lives in the sea. A prime example is the blue whale, which at more than 30 meters is the largest animal to ever have existed in the history of the planet.

But how should extinct marine megafauna be defined? “When we find a bone, we can’t always know how much the animal weighed,” explains the paleontologist. The lack of a definition for extinct marine megafauna was the starting point for her paper.

“We didn’t look at the weight but focused on the length of the extinct animals,” she says. “We counted all animals that were estimated to have grown up to a length of one meter or more as marine megafauna.” This is because even today, most marine megafauna is over one meter long, and there have always been animals in the ocean that were at least one meter long.

Based on this new definition, the paper aimed to provide an overview of 706 extinct marine megafaunal taxa, or groups of organisms with the same characteristics that differ from other groups.

Teaming up with students

The paleontologist knew that the task of listing all extinct marine megafauna would require a lot of work. She therefore decided to make this work the research component of her block course, which is designed to give students transformative learning experiences. She divided the students into groups and had them review all the available scientific information on the largest extinct mammals, fish, sharks, reptiles, invertebrates and birds that have ever lived in the oceans.

The conferences and the networks you build with other researchers are only a taste of the many aspects that make our job one of the best in the world.

Needless to say, the students were thrilled at the prospect of contributing to a scientific publication at such an early stage of their academic careers. Biology student Sabrina Kobelt, who was in the group researching mammals, says: “Catalina was very enthusiastic right from the start of the course and told us on day one that she wanted to publish a paper with us. My group spent three weeks scouring the internet for information about extinct prehistoric mammals, taking out books and compiling data on their weight, size and distribution.”

Once the list of species was gathered, the team quickly realized that more support was needed. So the UZH professor reached out to the students from the previous cohort of her block course and invited them to collaborate. “Catalina sent out an email to all of us asking who was interested and available to work on the project,” says biology student Janis Rogenmoser, who was in the fish research group. “I was happy to join. They sent us a list of fish, and then we independently collected information about these fish and recorded the data in a table.”

Mock conference

When it came to presenting the findings of the research component of the block course, Pimiento came up with a special idea to give her students a real taste of the world of science. “At the end of the course, students presented their findings at a staged scientific conference. And they took their role play very seriously.” The faux conference had all the hallmarks of a real one, including well-dressed participants, coffee breaks and a drinks reception at the end of the event.

For Sabrina Kobelt, the conference was one of the highlights of the course, and as in the real world, the informal part was just as important as the official program. “I particularly enjoyed the concluding apéro event in the Natural History Museum.”

Her fellow student Meike Günter, who was in the same group, has since gone on to take part in a “real” scientific symposium in London on the topic of human evolution and anthropology. “Everything was much larger and tightly scheduled, and there were several topics, whereas our course only focused on one specific topic. But the course was still excellent preparation for the real thing.”

The topic of marine megafauna lends itself to giving students a glimpse into the world of researchers, believes Catalina Pimiento. “Some students don’t yet know how cool science can be. The conferences and the networks you build with other researchers are only a taste of the many aspects that make our job one of the best in the world. That’s what I wanted to show the students in my course.”

Charismatic marine giants

It wasn’t just the conference that left a lasting impression. The students were equally impressed with their research topic. “My favorite fish to research was Dunkleosteus. It lived around 380 to 360 million years ago and had a kind of armor,” says Janis Rogenmoser. Meike Günter also remembers one species in particular: “There was a giant sloth that measured up to three meters and probably only lived in the sea or was semiaquatic. That was very interesting.”

Marine megafauna plays a fundamental role in the ecosystem. If their numbers decline or they go extinct, the consequences would be devastating.

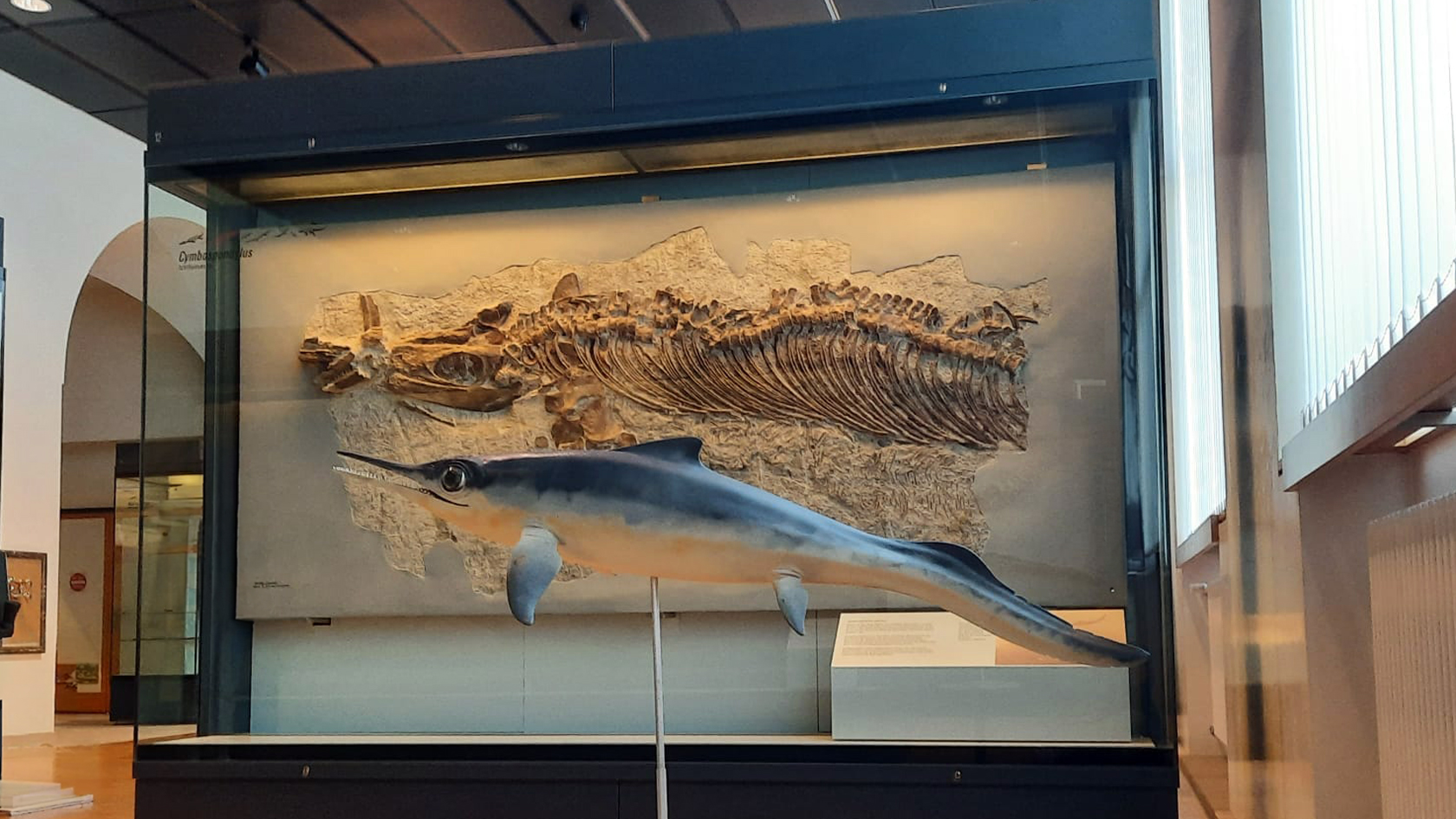

The largest of the extinct marine megafauna was Shonisaurus sikanniensis. “Shonisaurus was a marine reptile that could grow up to 21 meters long and puzzles us to this day,” says Pimiento. “We still don’t know much about its feeding. It would appear that Shonisaurus was an active predator, but fossils show that its snout was too narrow for this to be the case, and the adult animals didn’t have any teeth.” Nor was this ichthyosaur a filter feeder like the blue whale. “Shonisaurus probably fed on ammonites, snail-like animals that had a shell,” concludes the paleontologist. Fossils of other ichthyosaurs are on display at the Natural History Museum.

Important part of the ecosystem

Marine giants aren’t just fascinating creatures, they’re also a crucial part of Earth’s overall system. “The marine megafauna plays a fundamental role in the ecosystem. If their numbers decline or they go extinct, the consequences would be devastating,” says Pimiento. That’s why it’s as important as ever to study and protect these animals.