Under Suspicion

Cordula Haas of the UZH Institute of Forensic Medicine has a lot of experience in clarifying family relationships. Such investigations are a routine part of forensic genetics, but the stamp case posed an unusual challenge. Haas was tasked with finding out the paternity of Renc (names changed), born in 1886 in Austria-Hungary to young mother Dina. Two years after her son was born, Dina married her childhood sweetheart Xaver, who accepted Renc but believed that he was the son of a Jewish businessman, Ron, in whose household Dina had worked as a servant.

Xaver was living near his beloved Dina when Renc was born, but at first did not have enough money to get married. After progressing in his job, he made good and married her two years later. The newlyweds soon added another son, Arles, to their family. The truth about Renc’s paternity was kept a closely guarded family secret, not least because public disclosure could have put them in danger, especially before and during World War II, in view of Ron’s Jewish origins.

During World War I, Renc was called up and sent regular postcards to his future wife – the very postcards which have now brought the truth to light. Xaver always believed he was Renc’s stepfather – a story that was passed on from generation to generation, albeit with some niggling doubts.

DNA traces in the glue

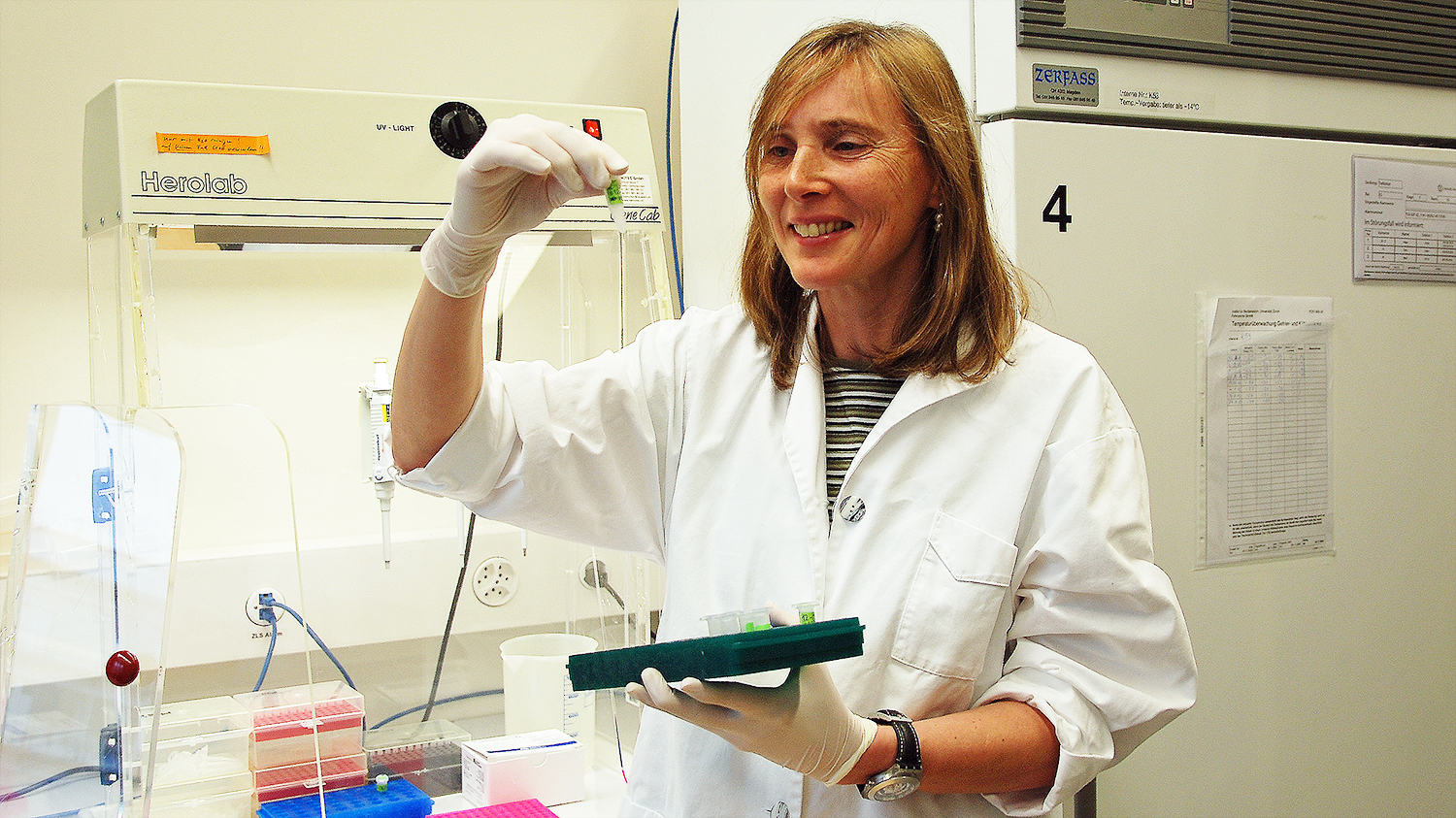

“When the descendants approached me five years ago to settle the family saga surrounding Renc once and for all, I knew it was going to be a difficult case,” says Cordula Haas. The geneticist has made a name for herself with analyses of ancient DNA, including studies of the almost 400-year-old skeleton of the Grisons freedom fighter Jörg Jenatsch (1596–1639). “I like unusual cases, they are always fun,” she says.

In Renc’s case, the problem was that evidence was required from three generations ago. The Y chromosome, which is passed down unchanged by males to their male offspring, is one way of tracing the lineage. But while the living grandchildren and great-grandchildren willingly provided tissue samples for DNA testing, there was no unbroken paternal line.

Renc himself had long since passed away, so it was not possible to get genetic material directly from him. “So I asked for personal items and postcards from grandparents and great-grandparents,” explains Haas. The experienced geneticist speculated that, with a little luck, the stamps would still contain sufficient intact DNA traces of whoever had licked them.

DNA traces are generally preserved in the glue of stamps, which protects them from harmful environmental influences such as UV light. Haas was taking a gamble, however, because genetic testing had never been done on such old stamps before.

In fact the relatives, who wish to remain anonymous, were able to find postcards sent by the supposed father, Ron, and by the son Renc. In the lab, Haas and her colleagues removed the stamps using steam and first checked whether saliva was detectable using an enzyme test. They then extracted the DNA from the glue, while taking strict precautions to avoid damaging it. “One of the biggest challenges in working with ancient DNA is the risk of contamination,” Haas says.

Excellent hygienic measures are therefore of utmost importance during the isolation and subsequent analysis of the DNA. However, because DNA degrades over time, it remains a matter of luck as to whether the characteristics being sought can be detected. In this case, the geneticists were looking for specific mini-satellites, i.e. short DNA sequences that are repeated several times. The combination of several such mini-satellites results in characteristic patterns for each person.

Success after five years

Cordula Haas and her team enthusiastically set to work, but after 18 months their efforts had come to nothing. The DNA of Ron, the presumed father of Renc, was so degraded that it was not possible to compare it with the other traces. Haas was ready to give up on the difficult case, but in 2020 the family combed through their belongings again and unearthed several more inherited items, including a card sent by Arles, Renc’s supposed half-brother.

Arles had sent the postcard from Rankweil (near Feldkirch) to his family in 1922. The analysis of his Y chromosome, almost five years after the start of the work, provided the definitive truth that came as a surprise to everyone: Arles and Renc were brothers, not half-brothers, and had the same father, Xaver. The analysis of the Y data proved this with a probability of 99.97 percent. The family secret turned out to be false.

A satisfying conclusion for Cordula Haas: “We were able to set the story straight after more than a century.” The findings are so unique and spectacular that Haas’ paper was accepted for publication in the journal Forensic Science International in November 2021. The case report is testament to how far genetic forensics have evolved in recent years.

The genetic fingerprint based on mini-satellites was developed in the 1980s by Alec Jeffreys in the UK. Incidentally, he also experimented with stamps, but much newer ones. Meanwhile, the sensitivity of the methods has increased enormously, and discoveries can be made with less and less initial material. However, points out Cordula Haas, the days of stamps providing evidence are numbered. We send fewer and fewer letters, and if we do use snail mail, it’s most likely a self-adhesive stamp. Text messages may leave digital traces, but not of DNA.

Note: All names of family members are fictitious.