“Photography is highly political”

Bettina Gockel, one of your research interests is the history of photography, which is a relatively young subject in art history. What do you find exciting about it?

Bettina Gockel: Photography concerns us all. It shapes our perception. In this sense, photography is a highly significant medium, both socially and politically.

How is photography political?

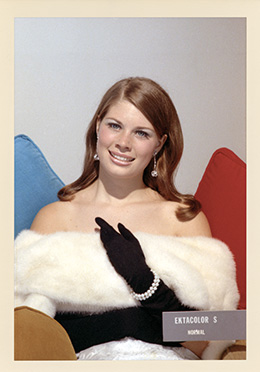

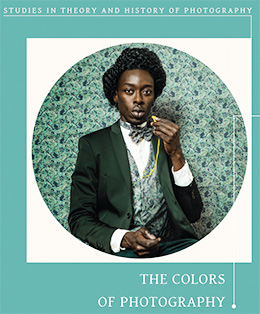

I’ll give you an example. Color photography used to be, and in some ways still is, mainly focused on white people. We may use the technology, such as cameras, but many of us don’t know how exactly the pictures were produced. In the 1940s and 1950s, for example, cameras and printers were calibrated using a white model. Photographic materials were thus designed to reproduce light (skin) tones. Dark colors were less detailed, and the facial expressions of dark-skinned actors or models were difficult to capture without special lighting technology.

Color film was based on the same standards. Modern cameras have a significantly higher color value range, but even current digital cameras distinguish colors based on brightness. There is a lot of criticism of this now from the black community, especially in the context of the Black Lives Matter movement. It’s an actual case of technological discrimination.

How do you convey such practical insights to your students?

By involving people who work in the field. I think it’s important to invite artists, curators, technicians and museum experts to UZH, and in this way make the diversity of our subject more known, internationally and across disciplines. With the Center for Studies in the Theory and History of Photography, I was able to bring visiting professors to the Institute of Art History for the first time, establish a visiting artist program and now also organize a visiting gallerist program, which will kick off in the 2021 Spring Semester.

Your predecessor at the professorial chair for the history of fine arts was art historian Franz Zelger. He had a background in museums. How has this shaped your work?

Bridging the gap between universities and museums is incredibly important. Without the knowledge of original and unique works, you can’t comment on the significance of art work. It’s also crucial to learn how to observe things in front of original works.

Franz Zelger practiced this with his students. But he also considered writing about art very important. He trained many students in museum work. I felt his work was a mandate for me to continue in the same direction.

What do students have to bring to the table if they want to study art history?

The field of art history has expanded in its scope and now also covers non-artistic media and imagery. This may intimidate students, but it can also be fascinating. I’m currently supervising a PhD project where the PhD candidate is investigating female self-representation on Instagram from a historical perspective. She’s relating pictures on Instagram to female self-portraits in 18th and 19th century painting. Such connections are new and exciting, and they also illustrate how much the subject has changed over the years.