“Teaching is Set to Become More Interactive and Intensive”

If AI can pen texts that are barely distinguishable from those written by a human, or a Google DeepMind program can achieve a silver medal score at the International Mathematical Olympiad, university teaching needs a rethink. “We can’t just keep doing what we we’ve been used to for so long,” says Abraham Bernstein, director of the UZH Digital Society Initiative (DSI) and co-author of a position paper by the DSI Strategy Lab on artificial intelligence in education, research and innovation.

The paper contains scenarios of how teaching and research might change given the rapid development of AI, and sets out recommendations on how the University of Zurich and universities in general can and should navigate it. “We don’t know exactly where the journey is headed,” says Bernstein. But the development is forcing universities to think about the near future, and ask themselves what their teaching will look like in a time when everyone can work with an AI tool.

Far-reaching recommendations

In the view of the experts who have been developing the scenarios and recommendations in a multi-stage process since last summer, one thing is clear: teaching is set to change fundamentally for all involved, instructors and students. The recommendations are therefore extensive, ranging from the form and content of individual courses, to the type of qualifications, and adaptations to buildings and infrastructure.

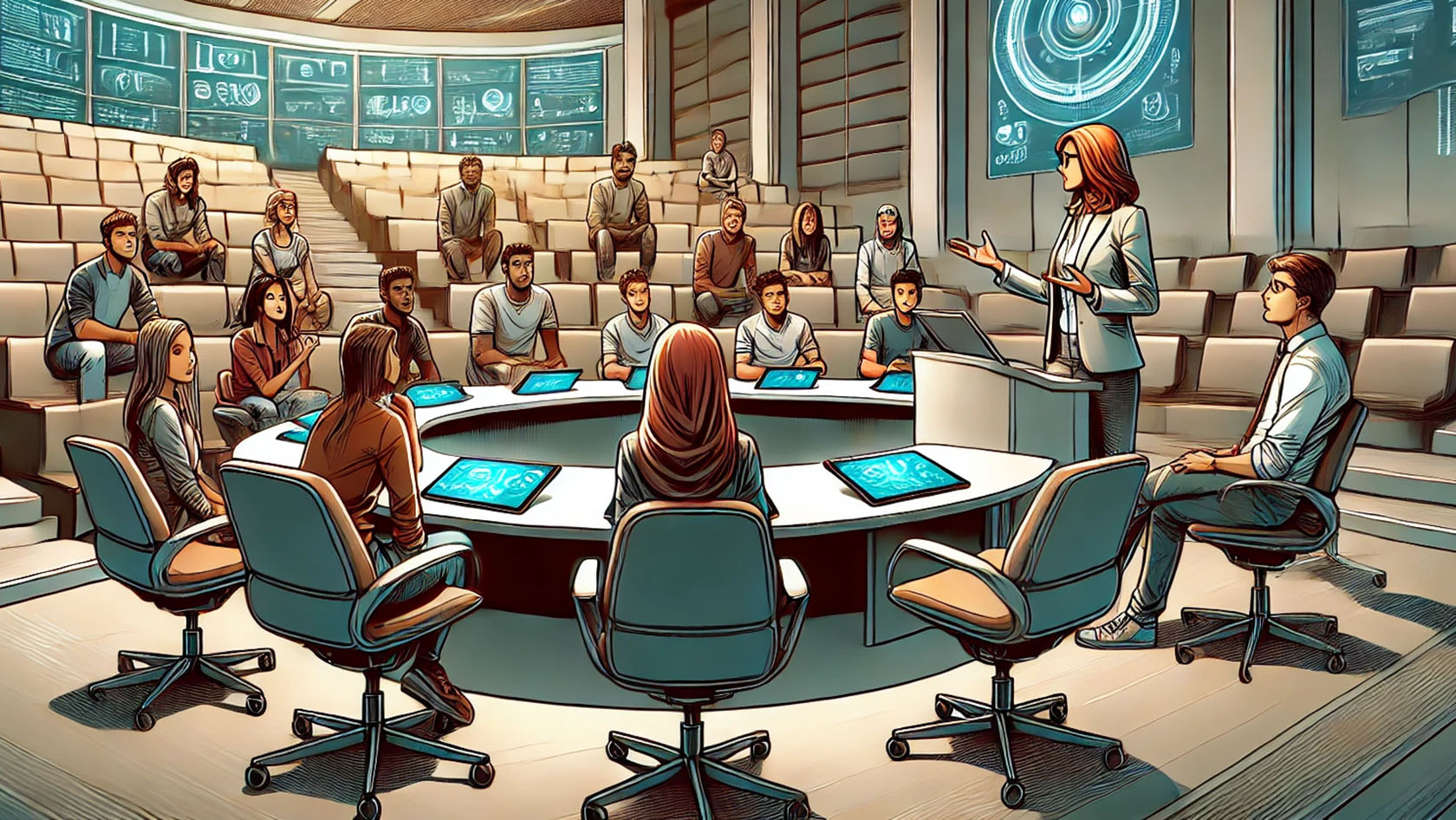

“Teaching is set to become more interactive and intensive”, says Bernstein. Instead of imparting pure knowledge content in large lectures, digital formats can increasingly be used, such as videos and interactive course units. In terms of courses, formats that prioritize interaction between teachers and students will become increasingly important.

Bernstein cites the example of the flipped classroom, where students are introduced to new content via videos and online learning. The actual in-person ‘lecture’ then focuses on active engagement with the material learned in this way. Depending on the level, the lecturer can answer students’ questions, work through tasks with them, discuss the material with advanced students, or work through case studies.

There’s a lot that we will still need to practice to support our cognitive development, even if machines can do it better.

More interaction – greater personalization

Bernstein sees this increased interaction with teachers and lecturers as a form of added value that the university will continue to offer, even in the context of digital tools. AI tools offer an opportunity here to make this interaction more personalized, even in large groups. “If we get to a point where everyone has an AI tool on their iPad that gives them personalized feedback while we all do an exercise, we can better address the disparities between students and provide them with more targeted support.”

For lecturers and instructors this means engaging with the new teaching formats. However, Bernstein believes that this will involve time and effort for teachers. Over the next few years, they will have to manage the transformation of courses, which will end up looking quite different from how they do today. In this regard, the university also needs to show understanding towards teachers and lecturers and give them the time they need.

Preserving critical thinking

Markus Christen, DSI Managing Director and co-author of the recommendations, sees the transformation as a gradual process that is already under way. “A lot is happening in terms of individual lecturers,” he says. Depending on the discipline, greater use is already being made of AI tools in teaching. He too has adapted the way he assesses performance in his courses. “Instead of writing an essay themselves, students now have to get an AI tool to write the essay using suitable prompts, and then critically reflect on it.” In this way, it is not only the content of the essay that is assessed, but also the student’s critical thinking skills.

Critical thinking is one of the abilities that must be retained in university education according to the recommendations. “There’s a lot that we will still need to practice to support our cognitive development, even if machines can do it better,” says Bernstein. People still learn mental arithmetic in school, even though computers can calculate much better and quicker than humans. But having an understanding of mathematics helps us check the plausibility of calculation results provided by a computer. Similarly, we need to retain the ability to assess whether AI output is plausible.

Besides critical thinking, the paper cites three other so-called ‘AI-hard’ skills that need to be retained. They are socialization skills and teamwork, the ability to handle uncertainty, as well as basic technical skills and an understanding of how AI technology works to be able to use the output from AI systems.

Universities need to maintain AI competencies and skills, so that we’re not completely reliant on external providers.

AI as critical infrastructure

The paper also looked at the impact of AI on research. “In the field of research, it’s important that we as universities understand what’s going on,” says Markus Christen. While AI tools have been used in research for some time already, they are increasingly becoming a critical infrastructure and should be seen as such by universities, say the authors in their recommendations.

This is why, according to Christen, it’s essential for universities to maintain AI competencies and skills, so that they are not completely reliant on external providers. Access to and usage rights for data and software licenses also need to be regulated. This shouldn’t be done at the individual university level, but rather in conjunction with other institutions, says Christen. “In this regard, all universities need to put their heads together – for example at the level of swissuniversities (the umbrella organization of universities and colleges in Switzerland).”

Autonomous player

One of the position paper’s predictions is that AI will increasingly become an autonomous player in the scientific community, with e.g. AI tools creating models and scenarios and increasingly suggesting relevant scientific questions itself. Universities need to recognize such processes and their impact on the role of researchers early on so they can help shape them in a targeted and proactive manner.

The recommendations of the position paper are in each case aimed at specific addressees, from Offices of Student Affairs to authorities and higher education institutions, such as swissuniversities.

“Implementing the measures and initiatives falls outside of the DSI’s remit,” says Christen regarding the next steps. The Strategy Lab’s position paper is designed to support stakeholders in their work. The fact that universities need to fundamentally rethink the way they teach and assess has been clear for some time, says Bernstein. “The emergence of ChatGPT has brought home to all of us the necessity of addressing this fundamental question.”