“Research isn’t a one-man show”

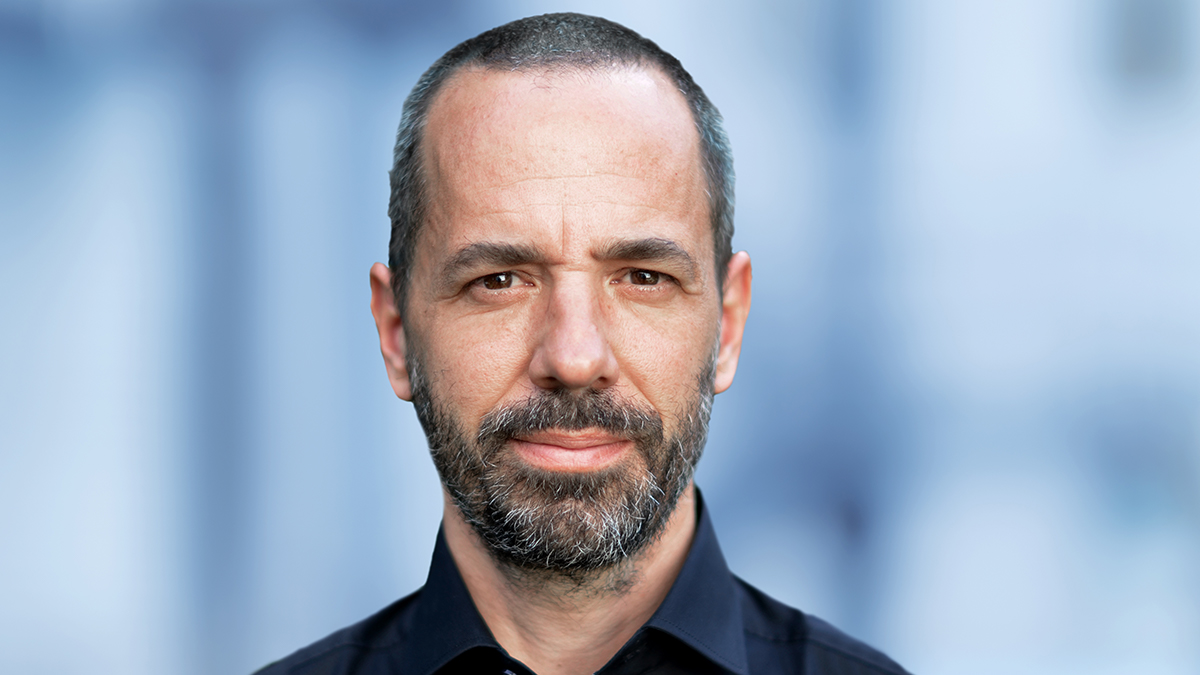

Moritz Daum, congratulations on taking over as executive director of the Jacobs Center for Productive Youth Development (JCPYD) on 1 August. What was the crucial factor for your appointment?

Moritz Daum: The Jacobs Center’s mission is to conduct research on human development with a focus on children and adolescents. As a developmental psychologist, that’s my specialist field. What sets the center apart is its combination of the areas of sociology, economics and psychology, with researchers from additional disciplines also contributing. This mandate to work together and the opportunities that come with tackling a scientific issue from different angles motivated me to get even more involved and take the reins of the center.

You’d like to increase the interdisciplinary nature of the center?

Research isn’t a one-man show any more. It requires team work that goes beyond the boundaries of your own discipline. Bringing together different disciplines is incredibly exciting, but it’s also a great challenge, since you have to find a shared language and common ground. I want to live up to this expectation and have people from different areas come together and interact.

The center used to have a managing director and a research director, but your new role now combines these two functions. Why?

When it was founded back in 2003, the center was headed up by one person. In 2015, there was a relaunch, and for the past two years the areas of management and research were split up to avoid overburdening a single person with the complex task of completing the expansion of the center. Now all professorships have been filled, and the processes are up and running. We can now go back to having a single executive director in charge of overall management.

The JCPYD is a joint venture of UZH and the Jacobs Foundation. Is the center’s academic freedom intact?

Yes, absolutely! Freedom of research and teaching is maintained in full and set out in a contract. We regularly exchange views with the Jacobs Foundation, and our communication is marked by mutual appreciation, but there are no entangled interests.

You mentioned the disciplines psychology, sociology and economics. Is the combination of these three areas unique?

Certainly in Switzerland, yes. You could draw comparisons with the Max Planck institutes in Germany, where specific topics take center stage. The three areas address human development from different angles and complement each other well. But it’s important to stress that these three disciplines cover only part of the science dealing with human development. Educational science and developmental pediatrics are important partner disciplines, for example. And biology, anthropology and language science are also tackling the issue. We’re working hand in hand with many different disciplines.

In which direction do you want to take the center? Which areas do you plan to focus on going forward?

As I said, the Jacobs Center is supposed to be a place where people with different backgrounds come together to work on projects. Interdisciplinary cooperation requires everyone to take a step towards the others. This interconnectedness within the Jacobs Center is very important to me.

How important is networking with researchers outside the center?

Our cooperation with multiple University Research Priority Programs, including the URPPs Adaptive Brain Circuits in Development and Learning, and Dynamics of Healthy Aging, as well as the NCCR Evolving Language shows that we have a good network outside of our center. I’d also like to mention the funding of a new research MRI scanner at the University Children's Hospital Zurich to facilitate new joint research projects. Promoting the Jacobs Center’s cooperation within and outside UZH is a permanent task.

How would you sum up the goals of your research?

Ultimately our research is about the search for universals and specificities. What do all people have in common when it comes to their development, and what is individual and the product of a person’s parents, language, culture and social environment? Our research aims to find effective interventions that will improve the lives of young people, even if basic research can’t always be translated into new educational concepts, for example.

Your own research is mainly concerned with the cognitive development of young children. What interests you in particular?

I’m interested in children’s social cognitive development. In other words, how do small children interact with other people verbally as well as non-verbally, and how do these forms of communication relate to each other, including from a cultural and multilingual perspective? These topics are highly relevant to society. Studies conducted in the 1970s, for example, suggest that the parents’ socioeconomic status has a major impact on a child’s language development; the higher the status, the larger their child’s vocabulary and the better their school grades, even though the children aren’t more gifted. But there have been other studies since then that show that these differences in levels can be countered if parents speak with their children often and also give them the chance to use their language. This is a good example of how a little effort can go a long way.

What are you working on at the moment?

Our research on multilingual language development is currently exploring the effect of children’s specific everyday experiences on the development of their communication skills. For example, multilingual children are more often faced with misunderstandings or frequently have to adapt to different languages in their conversations. Our research has shown that multilingual children are more sensitive to the needs of their conversation partner in their communication skills.

In 2019 your team launched the Kleine Weltentdecker app, which allows parents to answer simple questions about their children’s development on their smartphone. How is the project going?

The app is a kind of digital developmental diary and is now available in German, French, Italian and English. More than 2,500 parents are already using the app, some longer than others. By collecting this data, we are observing the range of development in children up to the age of six, which can vary quite strongly, based on a large sample size. At the same time we’re providing parents with information on the milestones in their children’s development. We’re constantly working to develop the app, and it has huge potential. For example, the app has already led to new projects with the Marie Meierhofer Institut für das Kind and the University Children’s Hospital Zurich (in the area of neonatology). This particular research project was established at the Jacobs Center in 2020, and ideally the app can also be used for other interdisciplinary research projects at the Jacobs Center in the future.