Like Star, like Planet

Tall people often have tall parents. Short people usually do not. What generations of humans had observed was finally explained by genetics: children inherit their parents’ genes and therefore share many of their traits. In some ways, stars and planets have similar relationships as parents and their children. For example, stars are older than their planets, they are larger and control much of what happens to the planets they host. Often, the star that a planet orbits is referred to as its “mother star”. But how much is there to this analogy? Do stars “pass on” some of their characteristics to the planets that orbit them – like, for example, their size? Researchers at the University of Zurich found that there is at least some truth to it, as their results published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics suggest.

A cosmic puzzle

"Over the last years, astronomers have found that more massive stars tend to host larger planets,” Michael Lozovsky, first author of the study, former doctoral researcher at the University of Zurich and associated with the NCCR PlanetS begins to explain. “While this seems intuitive at first glance, the reason behind it is not obvious and there haven’t been any rigorous attempts to explain it,” Lozovsky points out.

Unlike children, however, planets are not “born” by their star. Instead, they form from the same cosmic gas and dust. They do so with some delay – the stars begin to form earlier – but the star is often not mature while the planets begin to arise. A form of “heritage”, as in humans, is therefore not the reason that massive stars host larger planets.

But the following three theories that Lozovsky and his colleagues formulated could explain the pattern:

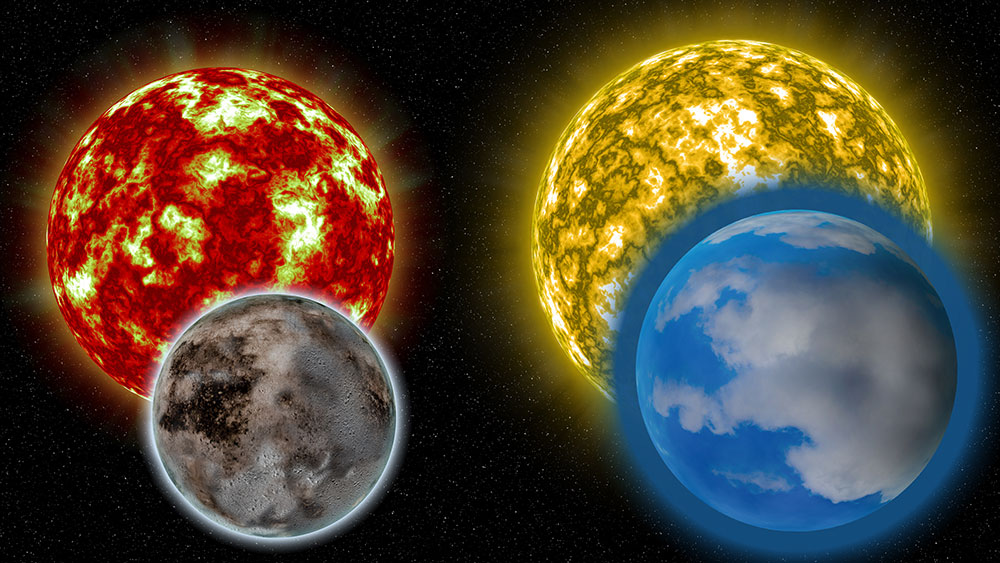

Planets around more massive stars are hotter: larger stars are hotter and emit more energy than smaller stars. This heats up their surrounding planets more strongly and as the planets get hotter, they inflate and become larger.

Planets around more massive stars are more massive: since the size of a planet increases with mass, it could be that stars that are more massive host larger planets simply because the planets themselves are also more massive.

Planets around more massive stars have lighter atmospheres: the atmosphere surrounding the planet can also be an important factor for its size. If larger stars tend to host planets with atmospheres consisting of light gases such as hydrogen and helium, this could also explain their larger size and the observed pattern.

Light gases make large planets

Using NASA databases, the team first looked at the available information on thousands of planets. Like for example temperature and size. “If larger planets were indeed hotter it would have been visible in the data. However, what we found was the opposite: hotter planets are sometimes even smaller, possibly because the strong stellar radiation evaporates some of their atmosphere,” Lozovsky says.

Testing the other two theories required more than statistics. “Using dedicated computer models, we simulated how planet sizes would change when their mass increased”, Lozovsky explains. What the team found, is that planets don’t become significantly larger for a given added mass but that they rather become denser instead. Therefore, the researchers also rejected this explanation and were left with the third theory, stating that the planets’ larger size comes from higher shares of light gases. “This time we found a clear signal – varying the planets’ compositions had a large effect on their size and could therefore explain the observed relationship to star mass. This also tells us that larger stars tend to host planets with more massive atmospheres,” Lozovsky reports.

“The results not only help us estimate which kinds of planets likely orbit a certain star, but could also help us fill gaps in our understanding of planet formation,” co-author, NCCR PlanetS member and professor of computational astronomy at the University of Zurich, Ravit Helled points out. Based on their findings, the researchers conclude that planets around larger stars tend to collect gases more quickly during their formation. This is important, because the gas and dust from which the planets form, begins to evaporate as the star grows and radiates more strongly. Thus, the planets only have limited time to grow and acquire what they need for their later existence – perhaps not entirely unlike children, who are expected to stand on their own feet eventually.