Navigation auf uzh.ch

Navigation auf uzh.ch

Quick action is vital after a stroke or accident involving paraplegia: Surgery and medication in the so-called acute phase, followed by rehabilitation. If the loss of nerve cells has led to speech or movement disorders, there’s only one thing for it: Patients have to exercise, exercise, and exercise again. Training encourages certain parts of the brain to take over the functions of the injured areas, enabling deficits to be offset to some extent. But it’s still not clear precisely what exercises work best for each patient, and how long they should train to gain the maximum benefit. This is what the scientists working on the Neuro-Rehab CRPP want to find out.

The researchers are using magnet resonance imaging (MRI) techniques in an attempt to work out the commonalities and special characteristics of neurological disorders, and they want to investigate the effects of sports training on the brain. In addition to paraplegia and strokes, the neurological diseases and disorders they’re examining include multiple sclerosis and Parkinson’s. They don’t only affect adults, but children and young people as well.

“We’re doing pure research, but always in relation to the patient; the benefit to patients is the most important goal of our research,” explains UZH professor Armin Curt, head of the Neuro-Rehabilitation Clinical Research Center and director of the Spinal Cord Injury Center, Research, at Balgrist University Hospital. The co-chair of the CRPP, Andreas Luft, UZH professor of Vascular Neurology and Neurorehabilitation, is convinced that training motor skills after a stroke or other neurological problems is an essential and effective therapeutic approach. Luft primarily works with stroke patients, and wants to encourage them to get more exercise. To this end he and his team are developing motivational programs designed to get patients moving. “People who see their progress and are rewarded for their efforts are motivated to keep training,” says Luft.

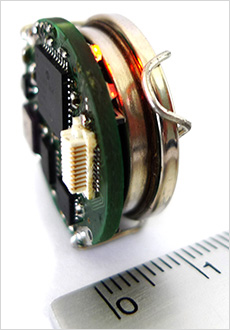

On the practical side the work also involves developing equipment to help patients with neurological disorders do a training program tailored to their needs, adds Armin Curt. Together with research groups at ETH Zurich they’re designing high-precision sensors that are so intelligently programmed they can be fine-tuned to the needs of the individual patient.

Built into exercise equipment, these sensors accurately record the patients’ motion sequences. For example they can measure how firmly a paraplegic patient is pushing their wheelchair, whether they’re maneuvering it properly and leaning into the bends, and how much speed and power they’re generating. The patient wears an easily attachable fitness band around their arm or leg. The commercial fitness bands currently flooding the market don’t capture data accurately enough to be any use for patients.

Beyond this, the researchers want to find out how much and for how long each individual patient should be exercising. The wristband provides valuable data. After exercise the data can be viewed on a mobile phone. On the one hand the data motivates the patient. But it also provides their doctor and the research team with important information on the type of exercise, the patient’s progress, and the effects of the training.

At the moment they’re testing a prototype of the fitness wristband, with the aim of marketing it soon via a start-up.

The wristband is only one example of the equipment being developed by the Neuro-Rehab research groups. They’re also working on developing and refining walking and arm robots.